In Sunday, Nov. 15, 15 Asian nations representing nearly a third of the global economy signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), forming the world’s biggest trading bloc. But one Asian economic giant was missing: India. Despite protracted negotiations, New Delhi refused to join the accord.

Once implemented, the RCEP will either reduce or eliminate tariffs on a range of goods and services and set up rules on investment and competition, and ensure protections for intellectual property. Economists and policy analysts have argued that India would in fact benefit from joining the RCEP. Besides the obvious upside to domestic consumers in the form of cheaper and higher quality products, the specific advantage of the RCEP lies in the opportunity it provides Indian firms to participate in global value chains and in attracting foreign investment. India’s experience with past free trade agreements shows that these deals have led to increases in exports to Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Cheaper imports of goods and industrial supplies from countries such as Japan have increased India’s productive capacity. Analysts have further argued that joining the RCEP would create jobs and sustain economic growth. There were compelling political reasons for joining the RCEP as well: Being a signatory would have given India the opportunity to shape the agreement in the future. And staying out of the deal isolates India, limiting its ability to shape the emerging trade architecture.

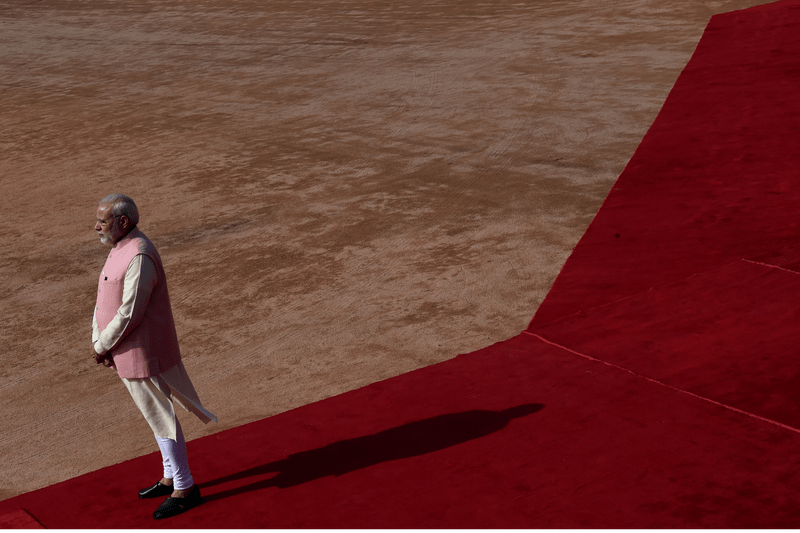

The potential benefits notwithstanding, India’s refusal to accede to the agreement was not entirely surprising. For decades, New Delhi has followed a highly protectionist set of economic policies as part of its historic commitment to a strategy of import-substituting industrialization. It was only in the aftermath of an unprecedented financial crisis in 1991 that the country gradually moved to dismantle an array of tariff barriers. Even though India’s integration into the global economy increased dramatically during the last 30 years, New Delhi’s rhetoric in trade negotiations has remained mostly protectionist. And this tone has become more pronounced during the administration of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, which focused on a “Make in India” strategy early in its tenure. Most recently, even before the coronavirus pandemic cratered the Indian economy, it announced a policy of economic self-reliance—atmanirbhar in Hindi—designed to boost domestic industry. In some ways, these policies harked back to a previous era when the pursuit of economic self-reliance was an integral component of India’s developmental strategy.

India’s refusal to accede to the agreement was not entirely surprising.

Aspects of India’s experience with free trade agreements have reinforced an ideological narrative of the importance of self-reliance. Even though the government’s own research has shown that India has, in sum, benefited from the trade agreements it has signed in the past, critics have pointed out that as a result of previous agreements, India has negative trade balances with several RCEP member countries. Critics have also linked such agreements, such as FTAs with Japan, South Korea, and ASEAN, to the decline of manufacturing in India. Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, India’s minister for external affairs, recently argued that trade deals have led to deindustrialization, and while the minister did not mention specific sectors, trade associations argue that industries such as electronics and light manufacturing have suffered on account of FTAs. There is no denying that policy and regulatory reforms and the effort to build a supportive infrastructure did not accompany past trade deals, limiting potential gains from FTAs. One of the biggest complaints is that the absence of safeguards in former FTAs have allowed an unchecked flow of Chinese imports into India.

Apart from the legacies of the past, both national political parties, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the principal opposition party, the Indian National Congress, despite significant other ideological differences, share a common distrust of free market economics. As a result, the BJP has faced little hostility from its most significant political rival when rejecting trade pacts. In fact, the negative tone of the narrative around past FTAs, many of which were negotiated during the Congress-led administration between 2004-14, might have led the opposition to vehemently oppose RCEP.

Both national political parties share a common distrust of free market economics. Apart from the ideological distaste of free trade there are at least two other compelling reasons for India’s intransigence. First, rapidly dismantling tariff barriers would prove costly for a number of Indian industrial enterprises that are not globally competitive. Unsurprisingly, significant segments of Indian industry, such as those of steel, plastic, copper, aluminum, paper, automobiles, and chemicals, lauded the decision to steer clear of the RCEP.

Second, India’s politicians are also beholden to India’s vast farm lobby. Many Indian farmers, for legitimate reasons, believe that a swift opening up of the country’s markets to foreign agricultural products could place them at a significant disadvantage. Large-scale reforms could prove costly—and even wipe out—the small, family-owned farms which dot the country’s landscape. Dairy farmers are particularly opposed to offering market access to foreign producers as they fear competition from the competitive, and more industrialized, dairy industries in Australia and New Zealand.

While there is significant opposition to RCEP from agriculture and industry, one would expect India’s service sector to advocate for joining the agreement. According to World Trade Organization data, India was the world’s eighth largest service exporter and ninth largest service trader in 2018 and is known as a powerhouse in the areas of information technology and business services. Indeed, Indian IT firms have lobbied for greater access into RCEP member country markets. But the nature of India’s IT exports involves cross-border movement of professionals. IT firms have, accordingly, sought concessions relating to restrictive business visa rules, statutory compliance costs, and domestic tax regimes, particularly in China. These issues tend to get embroiled in domestic immigration and regulatory policy debates and have proven to be particularly challenging to negotiate. While the RCEP has promised some service sector liberalization, member countries have not offered concessions on such cross-border movement of professionals, a key interest for India.

In other areas of service trade, India is more defensive and is not yet ready to open its markets. E-commerce is one such example in which India’s policy framework and lack of a regulatory environment prevents it from opening up its market. Other RCEP members have emerged as large service exporters. China, for example, is a prominent exporter of infrastructure, logistics, and technology. According to the same WTO data, China was also the fifth largest and the fastest growing service exporter in 2018. As this analysis of sectoral interests demonstrates, there is no strong constituency in favor of the deal while there are several vocal ones opposed to it.

Crafting a free trade deal with the United States will not be easy either.India’s exit from the RCEP may have as much to do with economic interests as it does with broader trade strategy and geopolitics. The Modi government has sought to reset its approach to free trade agreements by shifting its focus away from Asia to the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom. Such a strategy would counter those who argue that leaving the RCEP will isolate India with respect to multilateral trade agreements. However, as past experience has shown, crafting a free trade deal with the United States will not be easy either. Washington usually demands much higher standards in its trade agreements than what is present in RCEP, a requirement that is particularly true of issue areas such as investor-state disputes and intellectual property rights.

New Delhi has gambled that by not joining the RCEP and building a self-reliant India, it would be in a position to craft future FTAs from a position of strength. That is an unlikely scenario. As China’s accession to the World Trade Organization demonstrated, joining an existing deal requires paying a higher price in terms of trade concessions. Further, not joining RCEP robbed India of the chance to play a role in setting norms in new issue areas in trade such as e-commerce.

Building an economically strong India requires reforming New Delhi’s policy and regulatory environment and revisiting and renegotiating past agreements. Staying out of new ones is not the answer.