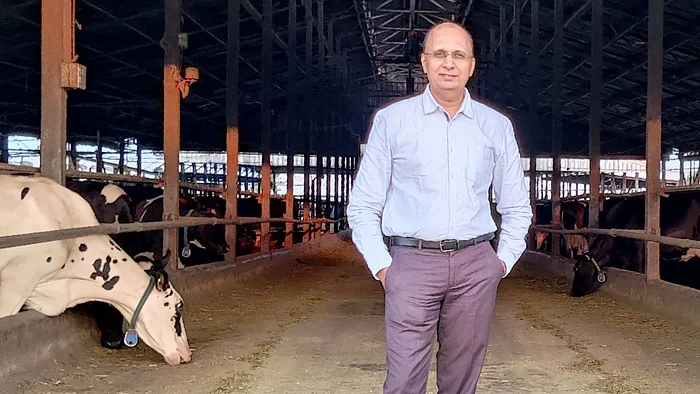

“Your brand is like the iPhone of milk.” Nitin Sawale grins as he shares a satisfied customer’s comment. This is feedback on packaged milk from Sarda Farms, a 50-acre Nashik-based enterprise which have been delivering the white stuff to thousands of Mumbai homes.

Nitin, 53, CEO, Sarda Farms, sees the humour of comparing milk with one of the world’s most premium brands but still can’t resist telling me about it.

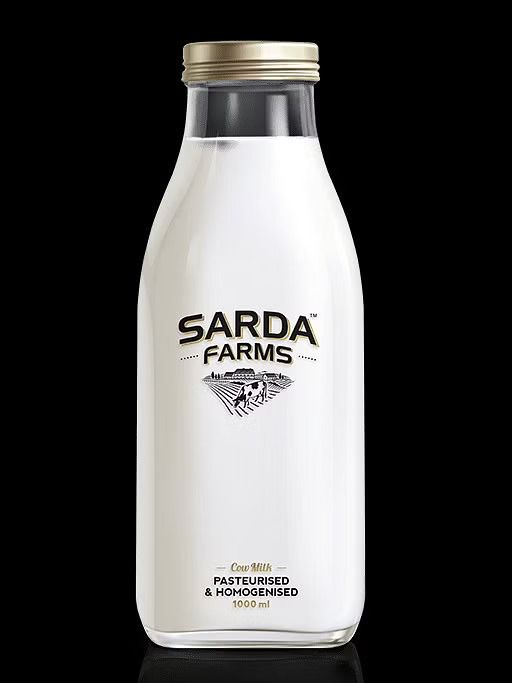

How does Sarda Farms manage to charge such a huge premium for a daily necessity? Milk is milk is milk. It doesn’t have ‘features’. (For the record, the standout brand identity and packaging design for Sarda Farms has been done by Alok Nanda & Co, a Mumbai-based brand consultancy)

At least as far as premium goes, the comparison is not entirely facetious. Whereas the typical trusted milk brand such as Amul retails for Rs 63/litre, Sarda’s comes for Rs 105/litre – a premium of almost 70 per cent.

“Dr Verghese Kurien created the quantity revolution in milk in the ‘70s. What we need now is a quality revolution,” believes Nitin Sawale, CEO, Sarda Farms.

About 10,000 households in Mumbai would disagree. They pay that premium day after day for their ‘subscription’ to the milk from Sarda. Households have to pay an advance of at least Rs 3,000 if they want to receive a litre every day. An app allows subscribers to increase, decrease or cease supply as they want.

I was drawn to write about Sarda Farms because I’d seen its distinctive bottle – somewhat round, somewhat square, or both perhaps – over the years at a relative’s place in Mumbai.

“Dr (Verghese) Kurien created the quantity revolution in milk when he launched Operation Flood in the 1970s,” says Nitin. “What we need now is a quality revolution.” He points out that sampling by government authorities often reveals inconsistent and substandard quality of milk.

Common complaints about milk relate to traces of the hormonal injection that farmers use to boost productivity. Antibiotics used to treat cows also can find their way into the white liquid.

Sarda Farms is one among a number of private player trying to create a market for the discerning milk consumer. It is also among the oldest. Though the market for milk and milk products is enormous, it is dominated by trusted brands such as Amul and Mother Dairy. Plus there are many large, regional players. How can new, premium brands break in?

It is a long-haul game but one with huge potential. Also, milk naturally lends itself to a subscription model, creating business predictability. A typical household which buys one litre of milk daily generates steady business of Rs 30,000 per year for Sarda Farms. And homes don’t easily change their milk suppliers. This is a customer worth waiting for.

“Dependability is critical. We have never ever failed to deliver milk on a single day– not even during the worst of Covid,” emphasises Nitin.

If the maket potential is so great, why is Sarda’s milk business doing annual revenue of only about Rs 25 crore after more than a decade?

“Wait another six months,” promises Nitin, “and we will be ready to rock. We have been putting all the building blocks in place. As my boss, Shrirang Sarda (the head of Sarda Group) says, ‘We need to get every process right first. Scaling up is only a matter of writing out cheques.’”

The milk market is dominated by large, trusted brands such as Amul and Mother Dairy. How can new, premium brands hope to break in?

Ten years isn’t so long in the perspective of Sarda Group which has been around for nearly a hundred years. Its primary line has been bidi manufacture. Bidis are rolled at home by workers on a contract basis.

With the long-term prospects for bidis (and cigarettes) gloomy, the group was looking for a new farm-based opportunity where it could leverage the power of 20,000+ home-based workers – as well as its existing distribution.

Fifteen years ago, it decided on the dairy business as a vehicle of growth. So, Sarda assisted workers to buy cows. However, that didn’t work out. Why?

“We discovered that quality of the kind we wanted was impossible to maintain by aggregating milk, which is how the business is run in India. This system has two weak links: the first (collection) and the last (distribution). It renders adulteration inevitable. The more the middlemen, the greater the mess,” explains Nitin.

So, in the interest of superior quality, Sarda gave up the aggregation model a decade ago and decided instead to sell ‘single source’ milk – meaning, breeding the cows which would provide the milk. Theirs would be a farm-to-home business. Since consumer expectation about quality was changing in other product categories, the team believed that, sooner or later, a wave of well-to-do Indians would make the same demand in milk. When that happened, the market would be enormous.

From where it was located in Nashik, the company could tap into the neighbouring markets of Mumbai, Pune and Surat. But, as it turns out, the focus has remained on Mumbai, a 7 million-litre-per-day market. Sarda’s share is but a drop.

Milk lends itself to a subscription model. A family which buys a litre per day generates Rs 30,000 annually for Sarda. Better still, families don’t easily change their vendor.

After due research, the group imported 200 Holstein Friesian cows from The Netherlands in 2011 (they now number 1,500). Since it was the team’s first experience with the animals on scale, learning how to manage and grow production in a controlled environment was a painfully slow process riddled with errors. It took nearly five years to stabilise the farm. The task of finding buyers began only after that.

Why do households switch to a brand like Sarda? There are three types of people, reckons Nitin.

“The first is the discerning consumer, the one who wants the best in every aspect of life. This is the person we originally targeted,” says Nitin.

Over time, two other segments emerged. The first were those who sought purity in what they consumed: these were typically health-conscious buyers (who were also inclined towards organic foods). The second consisted of mothers of infants who were being weaned: they wanted to be sure that their babies were getting the purest possible milk. “These are women who’d buy Johnson & Johnson baby soap,” sums up Nitin.

Sarda Farms would like the packaging to be in line with its promise of product purity. Glass works best but returning the bottles every morning is not for everyone.

So, the brand introduced an elegantly designed paper carton – not Tetrapak – in which milk can be preserved for two days. Both bottle and carton are priced at Rs 105/litre.

When Covid exploded and incomes were hit, Sarda was forced to introduce a plastic pouch (Rs 86/litre). Nitin is unhappy about this format because it is not in sync with what the brand stands for. “We had no option,” he shrugs, “because the pandemic hit the income of everyone, including our customers’.”

The last bit that Nitin and his team are working on is scaling up demand in a cost-efficient way. So far, growth has come via referrals: if a new referred home is given a trial supply of milk for seven days, there is a 40-50 per cent chance that it will be converted.

There are three types of people who buy Sarda’s milk: One, the discerning buyer; two, the health-conscious citizen and third, young mothers who are weaning their babies.

But referrals is a slow process. Sarda Farms is now trying to give a taste of its milk to Mumbai consumers, using a housing society as a target unit. “The advantage of this approach is that the growth is modular and we can scale it up as needed,” says Nitin. When they tried to give unlimited supply for a week, the conversion rate was about 8-10 per cent. Now Sarda is trying to limit supply to only a litre/day for a week – and the hit rate is still the same.

Sampling is one of the oldest tricks in the trade. The only difference is that Sarda is trying to keep the entire experience – except the actual milk supply – digital. Society members have to download the app and place their requirement on it.

Looking at the slow pace of Sarda Farm’s growth I am reminded of the early days of Café Coffee Day which kept tinkering with its offering for six years in its home city, Bengaluru, before it began growing rapidly outside it.

Will Sarda Farms remain a small, premium, niche player? Or will it capitalise on its deep, decade-long experience to grow the segment it so believe in?

I am curious to see how the Sarda’s ‘one-source’ milk story turns out.