USDEC previews key factors that will impact U.S. dairy trade.

Note from Krysta Harden, USDEC Chief Operating Officer: We’re all on the lookout for clues and indicators of where U.S. dairy trade is heading. The following analysis by USDEC Market Analyst William Loux is our annual look at the major factors that will influence U.S. dairy markets and export performance this year. No matter what happens, count on USDEC to keep a close watch on these and other developments in 2021.

At the start of every year, the U.S. Dairy Export Council publishes its ‘signpost’ article looking at the major factors that will impact dairy markets and trade in the year ahead. Like signposts on the road, these markers will guide dairy markets in the year ahead.

How much milk Is too much?

Aggregate milk production growth from the “Big Six” global dairy suppliers—New Zealand, the EU (including the UK), the United States, Australia, Argentina and Belarus—grew more than 1.4% in the first eleven months of 2020. While that was the highest gain in the last three years, adding over 4 million MT of milk to the global pool, a 1.4% increase is in line with global demand growth in a normal year.

As we know, 2020 was anything but normal. Yet, pandemic-related consumer economic support programs and end-user stock-building to ensure supply continuity in the event of further lockdowns and trade disruptions helped markets maintain balance—even as milk production momentum grew in the second half.

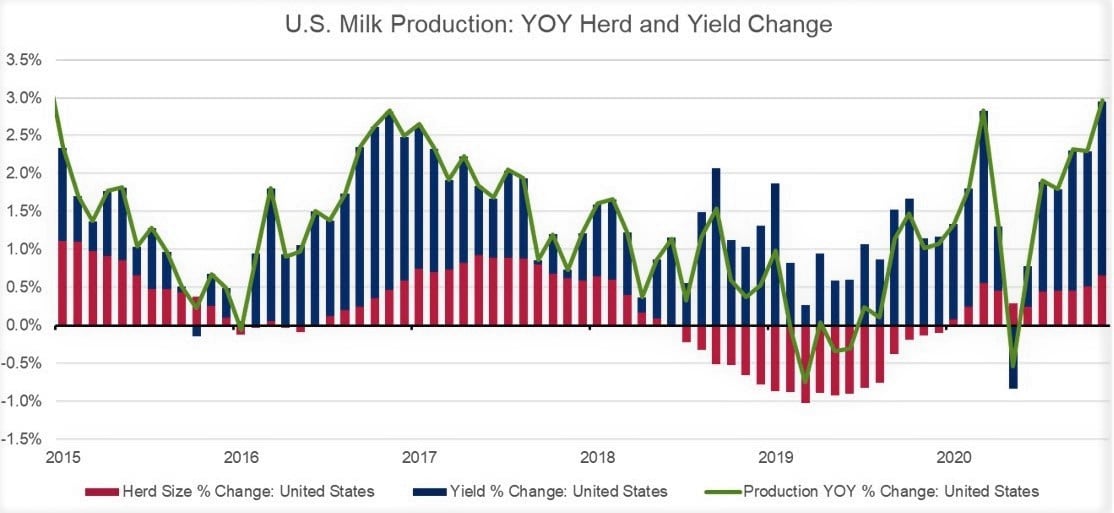

Second-half milk 2020 output growth accelerated largely due to the United States. Buoyed by pandemic-related government support programs, rising cow numbers and greater production per cow, U.S. milk production was running more than 2% greater July-November vs. the previous year, including a 3% increase in November.

U.S. was not alone: healthy farm profitability across most major milk sheds gave the production green light to producers from the EU to South America to Oceania to China, leading to broad-based growth. If poor weather had not dampened New Zealand’s spring flush, second-half expansion would have been even higher.

So what volumes can we expect this year, and will it be too much?

At the start of 2021, most of the factors supporting milk production growth last year remain in place. In addition, while weather is still a wild card, the La Niña threat that played a role in New Zealand’s hiccup in 2020 is waning.

Based on early signs, we expect strong milk production growth in the first half of 2021, particularly out of the United States, similar to what we saw in the back half of 2020, or around +2%. While expansion should ease in the second half, the question remains whether it will tip the scales toward oversupply in a year where questions abound about the pandemic, global economic health, global foodservice demand, export logistics and other issues.

New government, new types of support?

With so much new milk inbound, at least here in the United States, demand must grow to keep the markets in balance.

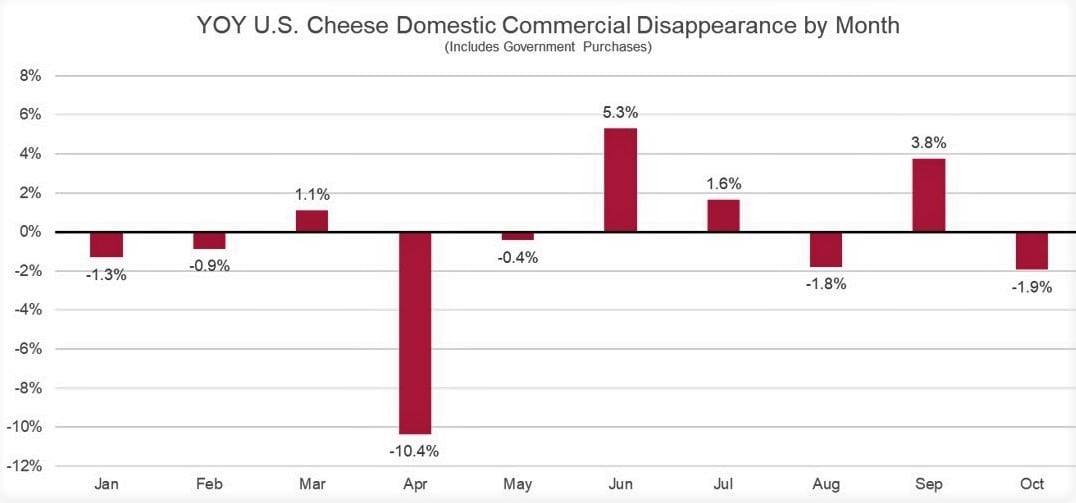

In 2020, the government was one of the more bullish factors in dairy markets. The most notable instances of government involvement were two rounds of payments to farmers as part of the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP) and the emergence of a new food aid program in the Farmers for Families Food Box Program. The Food Box program certainly succeeded in its aim to provide food to families in need and support to agricultural markets. However, the cost of doing so and the uncertainty of funding caused historic levels of volatility in the U.S. cheese market.

As we move into 2021, much needs to be ironed out, but what is known is that several provisions in the latest stimulus package will impact dairy markets. First, dairy farmers will receive an additional round of direct payments from the CFAP program. Second, dairy margin coverage will be adjusted to include additional coverage for farmers who expanded their milk production since 2019.

Both of those programs will incentivize greater supply. There are demand-supportive programs as well: an additional $13 billion for nutrition programs and an additional $400 million for the Dairy Donation Program.

Most notably, USDA announced the Food Box program will continue in the new year, at least through April, with an additional $1.5 billion in funding for product purchases. Not only is that a significant sum but with it concentrated in the first quarter, U.S. cheese markets received a strongly bullish signal in the near term.

However, once we move beyond April, future funding becomes murkier. Even with the Food Box program confirmed, the incoming administration will still have about $10 billion in unallocated funding to support agricultural producers. The future use of this money will be a key signpost for the year ahead.

Foodservice recovery

If the food box program or something similar is not continued throughout 2021, then U.S. domestic demand will need to pick up to keep markets in balance with plenty of milk forecasted. The primary guide for domestic consumption to watch in the year ahead is whether Americans return to dining out as many get their vaccine.

Total foodservice spending in the United States dropped dramatically from pre-pandemic levels as total food away from home spending fell 26% from March-October 2020 compared to 2019. The decline in foodservice was lessened over the summer, but preliminary data suggests winter only exacerbated the decline in foodservice. The National Restaurant Association estimates 17% of U.S. restaurants have closed permanently.

-1.jpg?width=554&name=Chart3%20(2)-1.jpg)

Still, at least for dairy, the combination of retail and government purchases has been enough to keep demand relatively supported since March. Total cheese consumption stayed close to level, declining 0.4% from March-October. And despite heavy bulk butter inventories, total U.S. butter consumption still rose 5.4% as consumers baked more at home. But if government support wanes in 2021, then those figures could drop unless foodservice recovers. For that, we likely need warmer weather or more vaccines to be administered.

Economic impact delayed or avoided?

While U.S. government action and the recovery of foodservice will play major roles here in the U.S., developments in the rest of the world will be crucial to global dairy markets and demand for U.S. dairy exports.

In 2020, pandemic-induced recessions did seemingly little to dampen global dairy demand, with global dairy trade up 5% through October. For many countries, economic performance in 2021 should be a clear marker of whether dairy demand can avoid recessionary impacts.

.jpg?width=1113&name=Chart4%20(3).jpg)

Plenty of macroeconomic forecasters are expecting a strong recovery in the year ahead for the global economy, but we shouldn’t expect it to be uniform.

In the United States, the economic recovery the country enjoyed over the summer and fall slowed sharply toward the end of the year with decelerations in consumer spending and employment growth. A prolonged recovery could mean that Americans could eat more at home, even after receiving their vaccine, in the year ahead.

More optimistically, China’s rapid economic recovery in the back half of 2020 – thanks in part to its aggressive control of the virus – helped strengthen the global outlook and provided a boost to many countries that rely on Chinese growth, especially in Southeast Asia. The latest IMF forecast projects China will grow by 8.2% in 2021 and ASEAN-5 economies will grow by 6.2%.

However, many economies remain in rough shape. Most concerning to dairy markets is the situation in Mexico. While Chinese and Southeast Asian dairy demand held up despite the pandemic, the same cannot be said for Mexico, where total dairy trade dropped by more than a quarter in milk solids equivalent. Thankfully, Mexico is unlikely to be heading for a third straight year of recession in 2021, but a weak labor market, struggling service sector and limited fiscal stimulus mean the road to recovery and pre-pandemic dairy demand levels could be long.

Much like in 2020, policy responses will certainly matter in the year ahead. Governments could continue to inject fiscal stimulus at the level they did this past year though political appetite and public debt will certainly play a role in those decisions. In the U.S., with Democrats gaining unified control of the presidency and both chambers of Congress, further fiscal stimulus seems plausible, though not guaranteed. If passed, an additional package could help avoid a recession-induced demand crunch here in the U.S.

Shipping/logistics issues

When the pandemic first emerged on the world’s radar, many analysts’ key worries were what impact labor shortages, container buildups and higher freight costs would have on conducting international trade. In Q1, this centered in China. By Q4, the issue had come full circle but with persistent problems focused on the U.S. West Coast.

Strong demand in the U.S. for imports, amplified by the recent holiday season and U.S. consumers spending more on goods rather than services, drove the delays. U.S. demand and rising freight rates from Asia to North America have created incentives for carriers to run empty containers back to Asia, rather than wait for U.S. export cargo. Add labor and equipment shortages, and all these factors result in a container build up in American ports, causing delays and adding costs for many U.S. dairy exporters.

Looking ahead to 2021, the situation is likely to persist into Q1, but a couple factors could help alleviate the crunch as we move later into the year. For one, the seasonal boom in retail around the holidays will abate. Additionally, as vaccines kick in, U.S. consumers may revert back to prior levels of service vs. goods purchases. Finally, albeit not positive, tighter wallets may result in reduced consumer demand.

Regardless, whether U.S. dairy exports must deal with higher freight costs or having to negotiate wider delivery intervals will be a key signpost in the year ahead for U.S. dairy trade.

China demand boom – Will it persist beyond Q1?

Beyond all the macroeconomic, policy or shipping issues, dairy markets will be guided by dairy-specific demand factors. In dairy, few markets can swing price and trade volumes like China.

That adage is especially true for whey products. In 2019, African Swine Fever (ASF) and retaliatory tariffs dampened demand for whey in China, especially from the U.S. Global whey shipments to China fell by 22%.

By 2020, with the U.S.-China Phase I agreement in place, a recovering pig herd by commercial operators and a desire for higher inventory levels, China’s whey market turned around, reaching a record in global trade volume and the highest prices in two years. Through October of 2020, global whey trade to China grew 54% and surpassed 540,000 MT on an annualized basis – 54,000 MT more than the pre-ASF peak.

Looking ahead to 2021, I am optimistic that China’s whey demand will continue to strengthen given that the nation approved permeate for human food applications last year, and commercial pig farmers that use whey in greater volumes now dominate the Chinese hog market. Additionally, pig pricing within China still shows that pork supplies are short, meaning there’s room for further herd expansion. Current whey pricing suggests export volumes should continue at pace at least through the first quarter of 2021.

However, the sheer volume China is currently buying does not seem to align with its current pig population, as few analysts believe China is near pre-ASF pig levels. Some of this could be that Chinese whey users bought when prices were low and are holding higher inventories. That should slow demand growth as the year progresses. As a result, dairy market observers should be on the lookout for when the rapid pace of demand growth returns to a more normal level.

-1.jpg?width=554&name=Chart5%20(2)-1.jpg)

China not only bought more whey in 2020, but it also bought more of all the major dairy staples, particularly milk powders in recent months. Chinese milk powder imports are highly seasonal, with most products imported in the first two months of the year. Early indications (Global Dairy Trade results, New Zealand November exports, high domestic milk prices, market anecdotes) suggest January and February of 2021 should be very strong indeed.

Still, it remains an open question whether China will keep buying aggressively throughout the year, which will be crucial to keeping the milk powder markets balanced, with ample milk production and clear demand questions from the major buyers. Thus, for whey and milk powders, China’s appetite beyond the first quarter will be a helpful signpost for the year ahead.

Southeast Asia – Can the U.S. sustain record-breaking market share?

Global dairy markets and trade won’t be determined solely by China’s activity. Southeast Asia will be equally crucial, especially for the United States. In 2020, the U.S. sold record volumes of dairy to the region, particularly NFDM/SMP. Through November, the U.S. exported 103,744 MT of NFDM/SMP, an increase of 50% over the next closest year, making Southeast Asia the largest market for U.S. NFDM/SMP.

While total NFDM/SMP trade to the region has been positive this year (up 3%), the biggest driver of the massive growth was a change in market share. On an annualized basis, U.S. market share finished the year just shy of 50%. Long-term investment in and commitment to the region by exporters and USDEC combined with favorable pricing and a trade dispute between the EU and Indonesia certainly benefited exports in 2020. Can we expect the same in 2021?

.jpg?width=554&name=Chart6%20(3).jpg)

U.S. investment and commitment are not going away and while pricing can fluctuate, current CME levels suggest favorable conditions for U.S. exports. However, the U.S. also benefited from its primary competition in the region – New Zealand and the EU – being occupied elsewhere. Strong demand from China and better returns meant New Zealand production favored WMP over butter/skim and the SMP it did produce still went to China over other customers. As mentioned above, if Chinese purchasing slows, more New Zealand SMP will find its way to Southeast Asia.

The story was similar for Europe in the Middle East-North Africa, where SMP volumes to the region grew despite being compared to 2019 (a year where figures were inflated by intervention product moving onto the market). However, MENA’s buying has slowed in the last few months, presumably after building more “just-in-case” inventories. If that slowdown continues in 2021, then the U.S. will encounter greater competition in Southeast Asia.

Still, the story is not just market share, as some regression to the mean is likely. For U.S. volumes to remain where they were in 2020 or grow, demand will need to grow as well. Over the past five years, NFDM/SMP has grown an average of 3% per annum. Whether Southeast Asia maintains or exceeds that pace in 2021 will be a key bellwether for dairy trade and markets, particularly of NFDM/SMP.

Mexico – Recovery or stagnation?

One of the biggest unknowns for U.S. exporters remains our neighbor to the south. Mexico’s demand took a hit in 2020 as a result of covid-19 exacerbating an already challenging economic situation. U.S. exports of cheese fell 1% through November, NFDM/SMP dropped by 14%, whey declined by 34%. The decline was not just due to the economy, as Liconsa, the state-owned company that supplies subsidized milk to low-income families, reportedly reduced imported NFDM volumes due its budget crunch and mandate to use more domestic milk supplies. With a long road ahead for vaccine distributions and economic recovery, a sharp resurgence in demand appears unlikely.

Still, considering the severity of the decline in 2020, particularly of NFDM, even a modest recovery in Mexican demand would be welcome and help alleviate pressure on NFDM markets in the event of a strong 2021 flush and intensified competition in Southeast Asia.

The direction of U.S. trade policy

We enter 2021 with a new U.S. administration taking the reins and the attendant policy uncertainty that usually surrounds such a changeover. USDEC is working on a range of fronts to ensure that incoming members of the administration and Congress are well briefed on the importance of trade to the U.S. dairy industry and the broader economy.

While no major trade deals are poised to imminently take effect, the trade policy agenda remains jam packed. The United States last year began talks toward new trade agreements with the UK and Kenya. The U.S., at the request of USDEC, is challenging Canadian tariff-rate quota allocation in the first-ever enforcement action under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement. The incoming U.S. Trade Representative has expressed a strong commitment to trade enforcement efforts—an element that’s critical to ensuring that we get the full benefit of the bargains struck with our trading partners.

We also need to continue discussions on trade relations with China (including on retaliatory tariffs on U.S. dairy products, which continue to hamper trade), on U.S.-EU trade relations and on rising trade barriers in Mexico. Plus, Trade Promotion Authority (which makes trade negotiations feasible) is due to expire in the summer unless renewed by Congress, and the World Trade Organization is awaiting new leadership.

It is too early to predict the outcome of these and other trade policy issues facing U.S. dairy suppliers in 2021. Still, market observers will need to pay close attention to trade policy in the year ahead as the implications could be significant. U.S. dairy competitiveness is a stake in many foreign markets. Ultimately, progress in new market opportunities or in other trade policy challenges will help determine the size and shape of U.S. dairy export opportunities well into the future.

William Loux is director of global trade analysis at the U.S. Dairy Export Council.