Wrestling with debt and struggling to adjust to consumer demands, America’s largest dairy producer filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection last week.

Analysts told Food Dive this news didn’t come as a shock. A number of factors led to Dean Foods’ decline, including dropping fluid milk consumption, rising competition from private label and milk alternatives, and a complex company history with M&A gone wrong and financial missteps from which it never quite recovered.

These factors culminated in a decline in revenues that led to the company’s bankruptcy filing after several CEOs failed to achieve the task of turning around the troubled business. Experts and analysts say what happened to Dean can serve as a cautionary tale to other businesses in the space.

“I don’t think there’s any question that Dean Foods is a casualty of the changes in consumer taste away from milk,” Kenneth Rosen, a partner focused on bankruptcy and financial reorganization at Lowenstein Sandler, told Food Dive. “I have to believe that if Dean Foods has been negatively affected by declining demand, other dairies have also been suffering. I have to believe that this is a warning sign to the industry that you better be really efficient if you’re going to survive.”

For decades, milk consumption has been declining and plant-based options have taken away some consumers who once turned to the popular drink. Non-dairy milk sales in the U.S. increased 61% from 2013 to 2017, while overall sales of dairy milk dropped 15% from about $18.9 billion in 2012 to $16.12 billion in 2017, according to Mintel.

“I don’t think there’s any question that Dean Foods is a casualty of the changes in consumer taste away from milk.”

Kenneth Rosen

Partner, Lowenstein Sandler

“Despite our best efforts to make our business more agile and cost-efficient, we continue to be impacted by a challenging operating environment marked by continuing declines in consumer milk consumption,” Dean Foods’ CEO Eric Beringause said in a statement as the news was announced.

The dairy producer said it plans to use this bankruptcy process to support its ongoing business operations and address debt while it works to sell the company. Dean Foods secured commitments for $850 million in debtor-in-possession financing, which is funding for companies in financial distress. The company, which owns brands like TruMoo and DairyPure, also said it was in “advanced discussions” to sell itself to Dairy Farmers of America, a co-op that sells milk from thousands of farms.

But how did Dean Foods get to this point? What’s next for the company? What can the rest of the industry take away from this? The answers are rooted in the company’s past, present and future prospects — and could pose a threat to the rest of the dairy industry.

Another dark chapter ahead for milk?

The company’s bankruptcy filing follows years of struggle for the dairy giant with competition from milk alternatives and deeply discounted private label dairy. These issues impact the fluid milk category as a whole — not just Dean Foods.

“In the case of Dean Foods, you have a confluence of things that have sort of caused the tide to go out: less milk consumption, more vertical integration and a shift to private label. All of those things have caused a situation where, unless Dean Foods can become much more efficient, it can’t compete. And that’s what happened,” Rosen said.

Last year, Walmart held a grand opening for its first U.S. food production facility, a milk processing plant that produces whole, skim and chocolate milk under its own Great Value brand. Kroger and Albertsons have made similar investments, allowing them to offer cheaper, similar products and reduce the shelf space for branded milk products across different retailers.

The company has also seen challenges from alternative milk. Plant-based dairy is in demand, with oat, almond, soy and other beverages gaining popularity. About 44% of milk-consuming Americans purchased both dairy and plant-based milk in the last year, according to a survey conducted by Dairy Management Inc.

And consumers are interested in these drinks for several different reasons. Last year, a Comax Flavors survey found almost half of consumers buy plant-based dairy alternatives for flavor (48%) and more than a third (36%) value the perceived health benefits.

Euromonitor analyst Simon Gunzburg wrote in a blog post that as many consumers turn to non-dairy alternatives like almond and oat milk, there is little opportunity for growth in traditional milk.

“Dean Foods’ bankruptcy filing is another page in the story of a struggling milk industry,” Gunzburg said. “…As dairy-free milk continues to shine in the spotlight with new entrants searching for market share and high profits, this news from Dean Foods illustrates the tough circumstances that lie ahead for those that rely heavily on the success of conventional milk products.”

Just last month, Dean Foods gave up its membership in the International Dairy Foods Association because it said the group didn’t share its priority of opposing the labeling of plant-based products with dairy terms. At the time, Dean’s stance could have been seen as a publicity stunt to draw attention back to dairy.

Mark Stephenson, director of dairy policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told Food Dive it has been known for some time that Dean Foods has been troubled, but there was no particular anticipation that a bankruptcy announcement was imminent. But, he said, Dean is heavily invested in a declining category.

“Consumer preferences have been shying away from beverage milk,” Stephenson said. “Whole milk has been a little bit more in demand recently and some other dairy products, but the whole category has been really pretty starkly in decline. So in a thin margin business in declining sales, that’s not a good recipe for a profitable business.”

The dairy category as a whole isn’t in as much trouble as milk. Stephenson said per capita consumption for all dairy products is higher than it’s been in years. According to USDA data, per capita dairy consumption in pounds per person has increased from 539 pounds in 1975 to 646 pounds in 2018, with more consumption of yogurt and cheese.

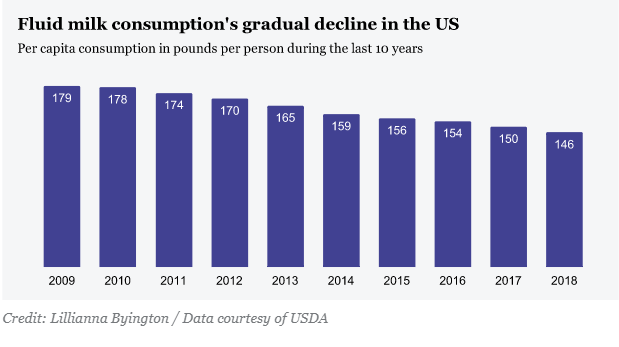

But Dean’s business is largely fluid milk and ice cream — two categories that have declined. Fluid milk per capita consumption has dropped from 247 pounds in 1975 to 146 pounds in 2018, and regular ice cream consumption dropped from 18.2 pounds in 1975 to 11.8 pounds in 2018, according to USDA.

“We look at the entire grouping of dairy products and I’m not as disappointed. I would be if I were Dean Foods. That’s certainly been disappointing and difficult for them, but from the standpoint of the dairy segment itself, not so bad,” Stephenson said.

As food companies work to adjust to rapidly changing consumer demands, innovation has been essential. That is difficult for milk though because chocolate is the only flavor that has really caught on, analysts say. But some companies have found innovative ways to produce and sell the staple beverage. Fairlife, a joint venture with Coca-Cola, produces ultra-filtered milk, a higher-protein and lower-lactose product that grew sales 42% in the first quarter of 2019 compared with the previous year, according to Food Navigator.

“Lessons can be learned from something like a Fairlife,” Stephenson said. “It’s not easy to find that growth segment, but apparently it’s possible.”

Matt Herrick, senior vice president of executive and strategic communications for IDFA, told Food Dive in an email the group doesn’t yet know the impact the bankruptcy will have on industry, but remains confident milk will continue moving from farmers to processors to retailers.

“Beyond that, it underscores what we already know — that we need to innovate to stay competitive,” he said.

Inside Dean’s complex history

To understand where Dean Foods is today, some analysts say it is important to look at the company’s corporate history.

In 2001, Suiza Foods Corp. acquired Dean Foods, its rival at the time, for about $1.5 billion. The merged company kept the Dean Foods name.

Andrew Novakovic, professor of agricultural economics at Cornell University, told Food Dive the acquisition joined two very different companies in terms of how they did business. Novakovic pointed to Dean and Suiza’s corporate history and management as a reason for Dean’s current struggles.

Founded in 1925, Dean Foods started in the Midwest and grew slowly and deliberately, he said. The company acquired family-owned operations with viable businesses and owners reaching retirement age. These companies often had strong local identities and brand names, and Dean would keep those in place.

“Unless somebody was paying pretty close attention, you might not even know that Dean Foods just bought the Mayfield Company, because the Mayfield brand is still out there, and a Mayfield plant is still there, and it would be kind of hard to notice,” Novakovic said.

“This might well end up being judged as an example of a company that grew too big, too fast, and perhaps didn’t pay as close attention to operating fundamentals as they should have.”

Andrew Novakovic

Professor of agricultural economics, Cornell University

This strategy made sense because fluid milk is really expensive to move over long distances, he said.

“They did this for decades in a slow and deliberate way and it wasn’t very sexy, but they had a strong business model and respectable earnings for a family-owned company,” Novakovic said.

Suiza, on the other hand, was the polar opposite, he said. The company’s leadership was primarily marketing professionals who were all about growing, buying and acquiring market share. They were not as focused on operational or financial management. Suiza went public in 1996 and just four years later, after 40 acquisitions, it became the country’s largest dairy processor.

In 2001, both analysts and the companies themselves said a Suiza-Dean combination made financial sense and could offer substantial cost savings.

“By combining with Dean Foods, we will … generate greater efficiencies and scale to invest in innovation and growth,” Gregg Engles, Suiza’s former chairman and chief executive, said in a statement 18 years ago.

But when the companies came together, Novakovic said the dominant culture of the new company came from Suiza and it wasn’t as deliberately focused on operations and finances.

“This might well end up being judged as an example of a company that grew too big, too fast, and perhaps didn’t pay as close attention to operating fundamentals as they should have,” Novakovic said.

After the acquisition, Engles became CEO of Dean Foods. He was known as a force in the industry as Dean’s stock price soared — until the company faced a series of problems.

In 2007, farmers filed a class action lawsuit against Dean Foods, National Dairy Holdings, Dairy Farmers of America and others for breaking antitrust laws. The complaint states that Dean agreed to make DFA farmers its only suppliers for low milk prices. Neither company admitted wrongdoing, but Dean Foods settled for $140 million in 2011. DFA settled for $168 million in 2013.

The same year the lawsuit was filed, the company announced it would borrow $4.8 billion, using $2 billion for a $15-a-share dividend. Investors were originally happy about the move, but then the financial crisis struck. The market crashed and the price of milk shot up, hurting Dean’s business.

During Engles’ tenure, his reputation went from being “milkman to the nation” to taking money for himself while his company suffered. Forbes ranked him among its Worst Bosses for the Buck in 2011, averaging $20.4 million in compensation over six years when Dean’s stock dropped on average 11% per year.

After its financial missteps, the company divested some of its assets. In 2012, Saputo bought Dean’s Morningstar division, which makes creamers and cottage cheese, for $1.45 billion. A year later, Dean completed its spin off of WhiteWave Foods to help its balance sheet. That fast-growing organic and plant-based food maker was acquired by Danone in 2017 for $12.5 billion.

In recent years, Dean Foods has worked to diversify its investments as milk has declined.

In 2016, Dean acquired the manufacturing and retail ice cream business of Friendly’s for $155 million. At the time, the acquisition aligned with Dean’s strategy of shifting its portfolio toward branded products.

The company also worked to expand its reach in the organic space. In 2017, Dean entered into a joint venture with Organic Valley to bring organic milk to retailers through Dean’s processing plants and it also bought Uncle Matt’s Organic, a maker of probiotic-infused juices and fruit-infused waters.

Also in 2017, Dean took a majority stake in Good Karma Foods, which sells flaxseed milk and yogurt. This investment allowed Dean to take a step into the alternative dairy space.

“Our investment in Good Karma is just one example of how we are executing against one of the major pillars of our strategic plan, to build and buy strong brands,” then-CEO Ralph Scozzafava said in a statement.

But these moves weren’t enough to turn around the business.

Dean Foods still has many contracts with dairy farmers. It cancelled more than 100 of those agreements last year to curtail how much milk it was buying as it moved to diversify its portfolio.

Stephenson said one lesson from Dean’s mistakes is about being careful with business. Dean Foods was “the darling of Wall Street for a good many years” while the company was in the process of consolidating and purchasing a number of different operations across the country. But that strategy didn’t pan out in the long run.

“When you’re not doing the growth through accumulating assets, but trying to find that growth in a category that’s stagnant to declining, that’s tougher to do. So I think any industry is going to have to look at that,” Stephenson said.

Why did Dean file for bankruptcy now?

In recent years, Dean Foods has been a sometimes painful display of the problems legacy food and beverage companies have faced.

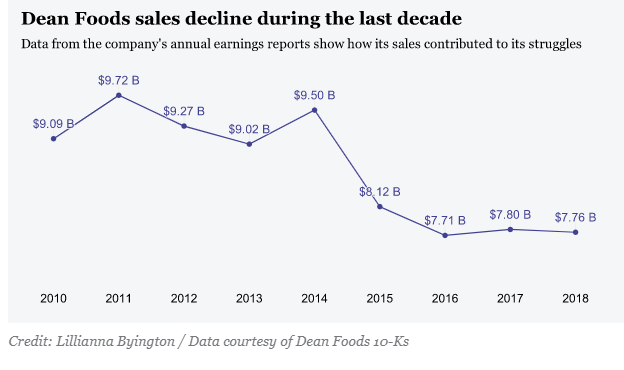

The company reported net losses in seven of its last eight quarters. In terms of management, Dean Foods has employed three CEOs in the last three years. With each turnover, the company faced more struggles.

Gregg Tanner, who had worked at Conagra Foods and Hershey, served as CEO of Dean Foods from October 2012 to December 2016 after taking over for Engles. He stepped down from the company three years ago, but remained an adviser until the next year. At the time, Dean Foods had nearly 17,000 employees and around $8 billion in annual revenue, according to The Dallas Morning News.

In January 2017, Ralph Scozzafava, who was serving as executive vice president and chief operating officer, took over as chief executive for Tanner. The company’s finances continue to drop. Dean Foods’ net income dropped from $61.6 million in 2017 to a loss of $327.4 million last year. Under Scozzafava’s leadership, the company increased its borrowing base availability to $265 million to enhance financial flexibility and liquidity as it faced continued financial challenges.

In July, Dean Foods announced Eric Beringause would replace Scozzafava as CEO. Beringause, who had 30 years of experience in the industry, said in the release announcing the change his top priority was “to ensure we have the right footprint and strategies in place to drive sustainable growth and profitability.”

So far, Beringause has not been able to achieve sustainable growth. Dean’s stock has been trading at less than $2 since April 24 and has lost about 98% of its value in the past year.

According to the company’s most recent quarterly report, Dean Foods has more than $1.1 billion in long-term debt, which is more than the company has had in the past five years. And in the release announcing the bankruptcy, Dean said it had approximately 15,0000 employees — roughly 2,000 fewer than reported in 2016. Last year, Dean Foods laid off hundreds of workers with the closure of at least five facilities.

“Since joining the company just over three months ago, I’ve taken a hard look at our challenges, as well as our opportunities, and truly believe we are taking the best path forward,” Beringause said in the release announcing the bankruptcy filing.

“It looks like the financials just sort of fell to the floor this quarter, and they opted to file as they ran out of liquidity.”

Bobby DeStefano

Distressed credit analyst, Debtwire

Bobby DeStefano, a distressed credit analyst at Debtwire, told Food Dive with the debts Dean had taken on and the sales declines, the company was getting to a point where it was “clearly unmanageable.” DeStefano said Dean shut down factories to improve gross margins, distribution expenses and sales. They arguably made some progress, he said, but it wasn’t enough.

“It looks like the financials just sort of fell to the floor this quarter, and they opted to file as they ran out of liquidity,” DeStefano said.

What would a sale mean?

Following a seven-month review, Dean’s Board of Directors decided against selling the company in September.

Instead, they entrusted the new CEO to turn the company around, saying Beringause would “provide the best opportunity to enhance long-term shareholder value.” This put a lot of pressure on Beringause, who just became CEO in July.

Despite Beringause’s years of experience, he decided the problems facing Dean Foods were too complicated to fix. Two months after Dean completed its strategic review, the company changed course.

In the release announcing the company’s bankruptcy filing, Dean Foods said it is in “advanced discussions” with Dairy Farmers of America for a potential sale. DFA, a co-op with 14,000 dairy farmer members and 47 plants nationwide, is accustomed to the issues facing the dairy industry. The co-op was formed 21 years ago, and its net sales last year were down $1 billion from 2017.

Monica Massey, executive vice president and chief of staff for Dairy Farmers of America, said in an emailed statement to Food Dive that since Dean Foods is the co-op’s largest customer, its focus is on ensuring DFA has secure markets for the co-op’s members’ milk. Although Dean Foods received bankruptcy court approval to finance its normal business operations, it seems like DFA’s priority as a potential buyer is to keep Dean operating.

“Thanks to the strategic planning and management by our farmer Board of Directors and management team, the cooperative is in a financial position to withstand a situation like this,” she said.

Cornell’s Novakovic said for any organization considering purchasing Dean Foods — whether it’s DFA or somebody else — the biggest question is whether they could do a better job running its assets. He said prospective buyers will look at what caused this problem and the intrinsic value of what the company has. DFA is a huge supplier to Dean Foods, which is both good and bad news.

“The bad news is they’re vulnerable if Dean Foods would completely default and not pay [farmers], that would be pretty big blow for DFA. Right now that seems pretty hypothetical, but it also speaks a bit to [DFA’s] motivation to take control of the situation,” he said.

“Dairy Farmers of America would have a big job on its hands to get Dean Foods growing again.”

Dean Best

Food editor, GlobalData

There could be other groups interested in the company. Canadian dairy company Saputo was rumored to be considering buying the company. Months later, the CEO told Bloomberg he wasn’t interested.

But now both Dean Foods and DFA have spoken publicly about the existence of negotiations, so they’re confirmed to be underway.

“However, even if a deal is struck, the combined business would still be operating in an ultra-competitive — and declining — market for liquid milk in the U.S. Dairy Farmers of America would have a big job on its hands to get Dean Foods growing again,” Dean Best, food editor at GlobalData, said in a release emailed to Food Dive.

But if Dean ends up not selling the business, DeStefano said Dean is going to look at how much debt the company can handle, what issues are causing Dean to burn through cash, and what’s the best situation the company can be in going forward. DeStefano said Dean will probably look at its business operations and assess its portfolio since under bankruptcy protection, the company might have a more leeway in shutting down certain facilities or selling off certain assets at a discount.

“It could go a number of different ways, but the objective is to treat the business and its stakeholders as well as possible,” DeStefano said. “People still need milk, so it’s not like it’s just going to go away.”

Overall, Lowenstein Sandler’s Rosen said Dean Foods is facing “a lot of problems” that likely won’t immediately change with a new owner.

“It will be interesting to see who buys this,” Rosen said. “Whoever buys it is going to have to figure out how to make money in a world where the market is not growing.”