With Fonterra announcing big write-downs on its asset values in China, Brazil, Venezuela and New Zealand, is it a fair question to ask what other assets elsewhere in the world might also need to be written down? Have we heard all the bad news?

The two biggest questions relate to Australia and Chile. These are Fonterra’s biggest overseas milk pools, which no longer fit clearly within the new emerging Fonterra strategy.

I recently wrote about concerns for Australia, where Fonterra has announced plans to write down assets by $70 million. In that article I expressed concern that much bigger write-downs might be needed.

Since then, my Australian network confirms that, particularly in Northern Victoria, Fonterra is indeed in big trouble, and heading towards more stranded assets. The problems are growing by the month. In July, Fonterra’s monthly Australian milk supply was 5.4 million kg milksolids (fat plus protein) whereas two years ago it was 8.3 million kg milksolids,

Fonterra is getting out-muscled for the dwindling Victoria supply of milk. It is already paying more than it can afford, and considerably more than its New Zealand farmers are getting. It is a mess.

But here, I want to focus on the Chilean operations of Fonterra. I see elements of an Australian mirror image, with Fonterra getting squeezed by poor market returns for its particular market products and dwindling milk supply from its farmers.

Although the big picture of Fonterra in Chile has great similarity to Australia, the details are different. The fundamental element in common is that Fonterra keeps getting thing wrong when it heads away from home, largely through inadequate understanding of the environment in which it is working.

The starting point for Chile is to recognise that Fonterra’s investments there go back to the NZ Dairy Board days. Fonterra inherited a majority share in Soprole, at that time Chile’s market-leading dairy company.

At the same time, Fonterra picked up a controlling share from the Dairy Board in Soprole’s little sister company Prolesur.

Whereas Soprole focuses mainly on consumer products produced and processed in the central parts of the Chilean dairy heartland, Prolesur is further south again in Los Lagos where it focuses on the commodity side of things, being mainly milk powder, butter, and more recently cheese. These are produced in high rainfall country, much of it around Osorno.

Then in 2009, Fonterra increased its stake to more than 99 percent ownership of Soprole and 86% ownership of Prolesur. And that is where ownership now stands. The purchase price indicates Fonterra’s Chilean assets were valued at around $NZ600 million in 2009.

To a large extent, Soprole and Prolesur operate as one company, with Prolesur’s profits incorporated into Soprole, and from there through to Fonterra. However, that is not the full story.

To start with, Fonterra has strongly encouraged Prolesur suppliers to focus on grass-fed systems and spring-calving as occurs in New Zealand. The Prolesur payment system has been aligned to this policy.

However, the realities of dairying in southern Chile, although having superficial resemblance to New Zealand, are not the same. Hence, Prolesur has now recognised that seasonal milking also has disadvantages, particularly when it comes to product marketing, and hence what it can afford to pay its farmers. Unfortunately, this understanding has been delayed.

It is readily apparent that Prolesur’s farmers are currently not at all happy. In the calendar year ending 31 December 2018, the Prolesur supply dropped 17.7 percent despite overall Chilean dairy production rising 1.9 percent.

It is also clear that many more of Prolesur’s farmers would leave Prolesur, and hence Fonterra, if they could. They would very much like to join Colun which is a Chilean dairy co-operative that has been smashing Soprole in the market place.

Although Colun is now Chile’s leading dairy company, it is capacity-constrained and has a waiting list of farmers. In consequence, southern farmers are having discussions as to whether they might set up their own co-operative.

Also, Prolesur’s minority owners are trying to sue Fonterra for unfair transfer-pricing of products across to Soprole, at prices that damage their economic interests. This legal challenge in itself has potential to be messy.

Prolesur recognised some years back that it needed to invest in cheese production. This has occurred in the north of Prolesur’s production region, with production capacity now at more than 2000 tonnes per month. This has exacerbated the supply problems for their milk powder production at Osorno, where they already have stranded assets.

Fonterra’s problems in Chile go well beyond Prolesur in the south. Big sister Soprole, which incorporates Prolesur within its own accounts, is also in decline.

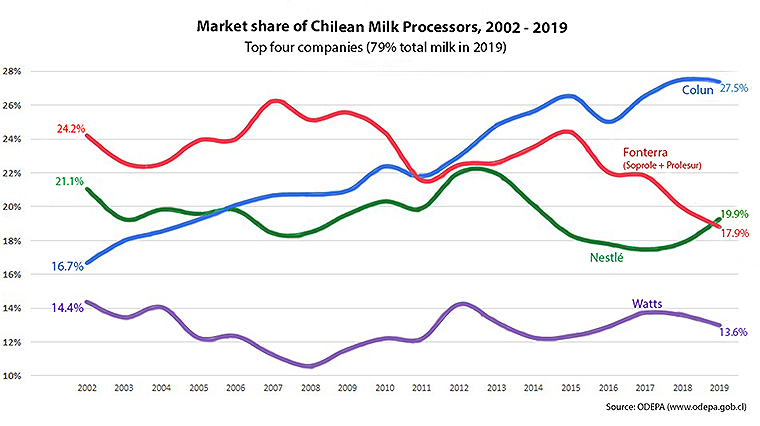

Chilean market-share data goes back to 2002, at which stage the Soprole plus Prolesur combination was number one in terms of national milk supply. As the graph shows, from there through to around 2015, it was a case of large swings and roundabouts, but arguably with no consistent trend in market share. Since then it has been an ongoing decline.

Right through to 2018, it may have seemed to those people who rely on published profit figures that Fonterra was doing OK. There were steady dividends back to New Zealand. For many years it was a great cash cow.

However, if Fonterra’s top managers and directors had been doing some independent foot-slogging they would have known that all was not well. I have seen correspondence going back to 2014 where Chilean farmers were trying to tell both Fonterra and the New Zealand Government that things were not right.

To put it in a nutshell, the Chilean farmers were accusing Fonterra of overmilking the Chilean cash cow. It was all short-term thinking.

Soprole produces accounts for each calendar year, in Spanish, and I have been trawling through those. The latest accounts are for calendar year 2018.

The numbers show that when converted to NZ dollars, the consolidated Soprole operation for calendar 2018 made a profit of around $55 million. The year before it was about $65 million and before that over $70 million. In 2015 it was $80 million.

Soprole currently has a book value, converted to NZD, of around $940 million. Equity is valued at around $700 million. It is hard to argue that the current profits are sufficient to justify these figures. Beyond that, the trajectory is wrong. No-one would buy assets at anywhere near that price.

Soprole brands are no longer considered premium brands in Chile. Some of Fonterra’s Chilean processing assets are less than efficient. Those assets belong to a previous era. And Fonterra lacks a loyal base of suppliers.

Put all of those things together, and look into the future rather than the rear mirror, and Fonterra’s Chilean assets look very shaky. Just like elsewhere in the world, Fonterra has dug a deep hole for itself.

It would have been much easier to not dig the hole in the first place than to now find a way out. The first step forward is for Fonterra to identify the extent of the hole.