The Harappan site of Kotada Bhadli contains the earliest direct evidence of dairy product processing, which may have played an important role in its survival and expansion.

The isotopic analysis of lipid residue trapped in Harappan-era pottery sherds in Gujarat unearthed what empirical facts couldn’t; the first direct evidence of dairy processing from Kotada Bhadli in Gujarat, dated to the second half of the third millennium BCE. With this excavation and the analysis from it, researchers opened windows to a period that had never been thoroughly explored.

The advent of agriculture ushered forth an age of change in human history. Sedentary life benefited our ancestors who could now control their surroundings, utilise resources and most importantly, domesticate wild flora and fauna to aid their subsistence. Human and animal relationships have been the most successful initiators of socio-cultural progress. Domestication of animals has been dated to the seventh millennium BCE in South Asia, based on evidence from the Aceramic Neolithic deposits (the early farming or Neolithic phase without the presence of ceramics in material culture) at Mehrgarh. Fragmentary bones and artefacts such as figurines were thought to be enough to decipher the complexities of the human-animal relationship that spoke of the utilisation of meat, dairy, hides and their strength for labour-oriented jobs. However, as demonstrated by the excavation at Kotada Bhadli, advancements in scientific analysis have revolutionised the study of historical objects, allowing scholars to delve deep into the core of pottery fragments and go beyond established archaeological facts to unearth more compelling evidence.

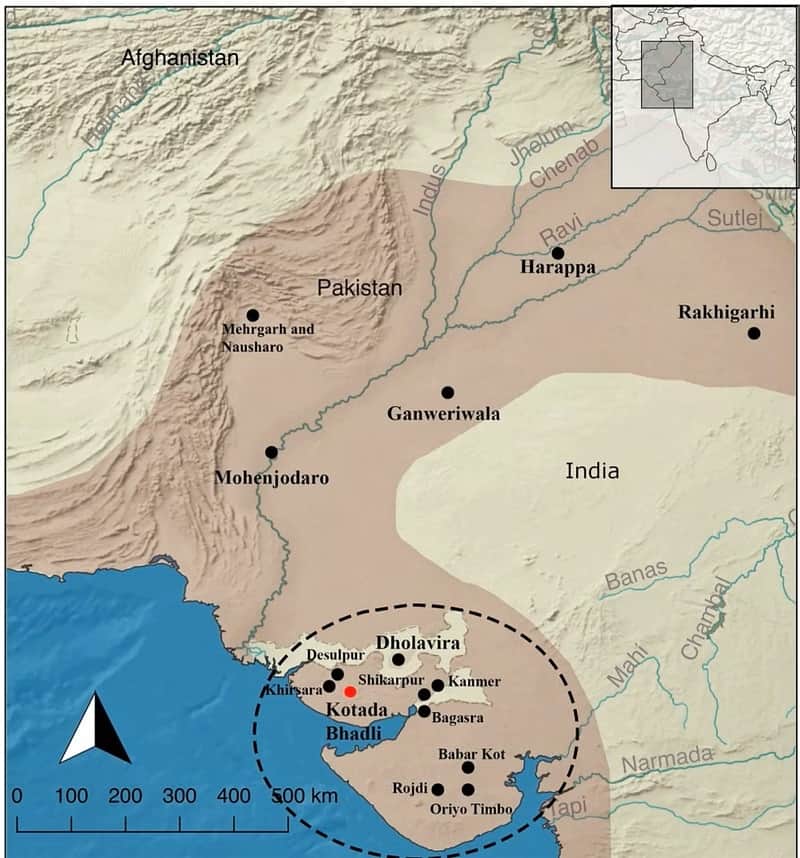

Located in the Nakhatrana taluka of Gujarat’s Kutch district, the site at Kotada Bhadli was excavated from 2010 to 2013 by archaeologists Prabodh Shirvalkar from the Deccan College of Post Graduate Research, and YS Rawat from the Gujarat State Archaeology Department. The excavations revealed that this was a rural Harappan settlement, dating from c. 2300 to 1950 BCE (late Mature Harappan period). The dig yielded a residential complex with nine rooms, a fortification and a bastion. A sedentary to semi-sedentary form of animal husbandry was the primary occupation here.

The period spanning from 2300 to 1900 BCE has never been explored and examined as thoroughly as with this site. This period is significant because it depicts the continuous transition in civilisation from the Mature Harappan and the classical age to the Late Harappan period. This excavation also focused on this humble yet dynamic rural site’s relationship with big settlements; perhaps large cities like Dholavira depended on it for economic contribution. However, the biggest contribution of this excavation is the isotopic analysis of lipid residue from pottery fragments.

What this lipid analysis means

In recent years, lipid residue analysis from archaeological vessels has been successfully used to determine aquatic product processing, cheese-making, processing of plants to produce alcoholic beverages and the type of oil used in lamps. Lipid analysis has also helped in the identification of resinous materials that have been used as adhesive and water-proofing layers on ceramic vessels. This tool has been successfully used to identify the sources of organic materials in wall paintings and ashy deposits from archaeological settlements.

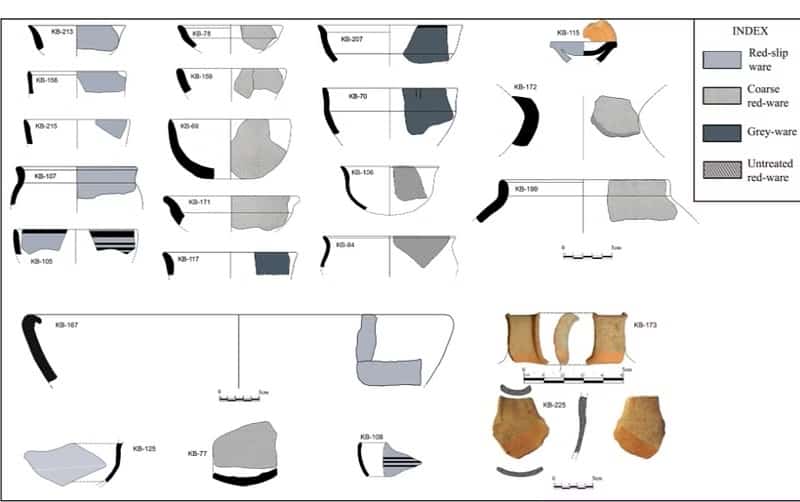

The Kotada Bhadli excavation analysed the absorbed lipid residues from 59 ceramics sherds recovered. One-step acidified methanolic extraction was the primary method used to extract absorbed organic residues from all 59 samples. Of the 59 samples examined, 21 showed signs of animal preservation. These samples indicated the presence of both ruminant and non-ruminant adipose fat (Bone marrow, for example) and ruminant dairy fat. It appears that all the ruminant dairy fats in the assemblage were exploited from cattle, some water buffaloes and possibly some sheep that primarily consumed C4-type vegetation (plants grown in tropical and dry environments). In the case of Kotada Bhadli, these would primarily be agricultural millet

The strontium isotope values from the tooth enamel of the primary domesticated animals from the site also indicated that cattle, water buffaloes, goats and sheep were possibly raised locally. For the uninitiated, archaeologists use strontium isotope ratios to determine ancient humans’ geographic origins or migration patterns. Next, the values emerging from carbon isotope analysis – which allows archaeologists to gain insights into past societies by studying carbon isotopes in organic materials – indicate that human-induced foddering played a major role in rearing these domesticates.

What the results reveal

Our knowledge of dairy exploitation during the Indus Valley Civilisation, particularly in South Asia, is limited. Numerous suggestions of dairy consumption during the Indus Civilisation have been made based on the mortality pattern of animals and by considering artefactual remains that may represent probable consumption of dairy products. However, none of these studies have provided direct evidence of dairy consumption during the Indus period. The only lipid residue analysis of Indus/Harappan vessels prior to this research was of a perforated vessel from Nausharo, which compared the fatty acid distribution of perforated vessels with fatty acids of dairy from modern farm animals, suggesting that these vessels were likely used for dairy product processing.

Therefore, this study on Kotada Bhadli samples reveals the story of various animal-exploitation tactics. This site contains the earliest direct evidence of dairy product processing; dairy may have been an important element of Kotada Bhadli’s daily diet – coming largely from cattle and maybe even from water buffaloes, who were not major domesticated animals in Kutch – perhaps playing an important role in their survival and expansion.

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and junior research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)