- Domestic makers of baby powder rebuild their market share to 44 per cent, all down to Feihe which was not caught up in the 2008 tragedy

- Foreign brands are seen as “way more trustworthy” and this reputation is likely to last for very long time, EIU says

Twelve years ago, 300,000 children in China were poisoned after drinking infant milk formula that contained melamine, a chemical used in plastic. Six babies were killed by the toxic substance, which was used by 22 companies to artificially boost the protein levels that showed up in nutrition tests.

Those responsible were punished with sentences ranging from lengthy prison terms to the death penalty.

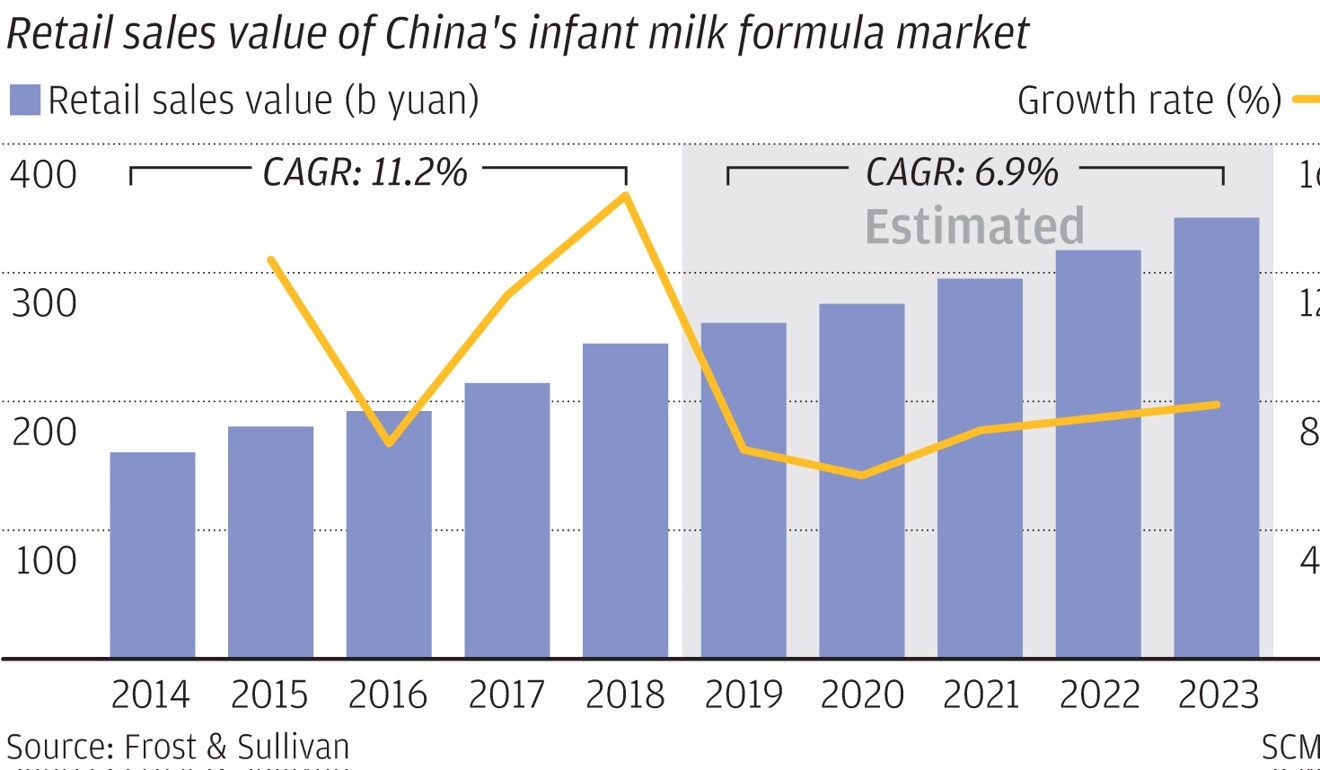

Dubbed the ‘melamine scandal’, the tragedy rocked China’s baby milk formula industry. Many parents lost their trust in domestic brands, paving the way for foreign companies to charge ahead in a market Euromonitor predicts will be worth US$32 billion by 2023. Only about a quarter of Chinese mothers breast feed.

More than a decade on, China’s dairy industry is still shrouded in mistrust. Its largest infant milk producer, China Feihe, is the only domestic baby powder company that has emerged largely unscathed, touted as the brand to take on international giants like Nestle and Danone. Feihe did not have any melamine in its products.

Analysts say there is still a way to go before consumers fully trust and actively choose domestic producers over foreign rivals, and that gains in overall market share by local companies in recent years are almost entirely down to Feihe’s success. Foreign brands say China is a hugely important market they intend to continue expanding in.

“Foreign brands are seen as way more trustworthy than domestic ones and this reputation is likely to last for a very long time, particularly for middle-class cities,” said Dan Wang, China analyst for the Economic Intelligence Unit (EIU). Anything that harms babies in a country that, until 2015, enforced a one-child policy, will destroy consumer confidence, she said.

Both Wang, and Robin Yuen, consumer analyst for Singaporean investment bank UOB-Kay Hian, said parents would choose to buy foreign-branded baby powder if they can afford it.

“Those in tier-1 cities, they still prefer the top international brands,” said Yuen. “A lot of the domestic brands are winning shares in the lower-tier cities.”

The government has also tightened its supervision and rules around the registration of infant milk formula companies and products, manufacturing standards and advertising practices.

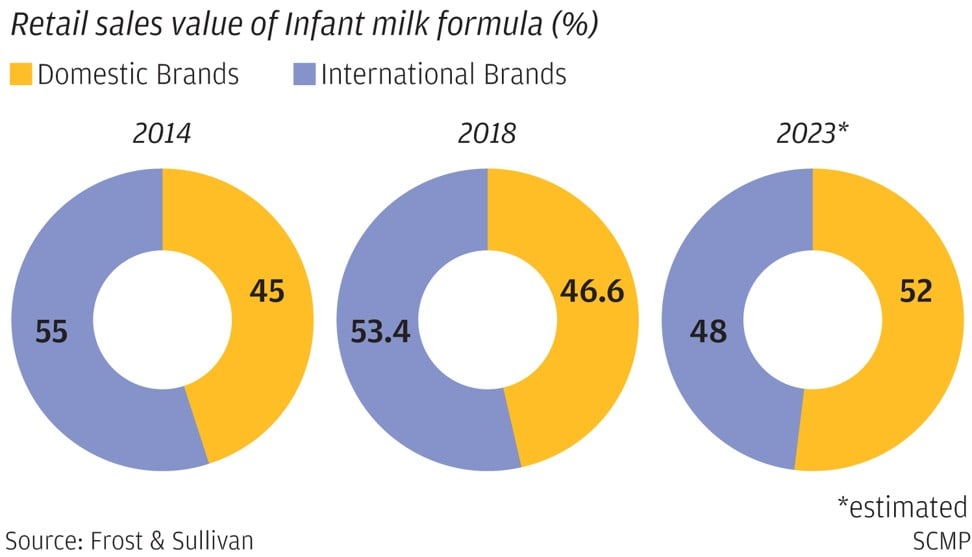

In 2018, Chinese producers accounted for 44 per cent of the domestic infant milk formula market, according to US market research firm Nielsen.

Feihe was the second-largest player among domestic and international companies, in terms of retail sales value, according to research firm Frost & Sullivan, with a 7.3 per cent stake in the market, up from 3.4 per cent in 2016.

Among only domestic companies it had the largest market share – 15.6 per cent in 2018, up from 7.4 per cent in 2016. Feihe saw revenue of 10.4 billion yuan (US$1.5 billion) in the same year, with premium infant milk accounting for 64 per cent of that. Net profit was 2.2 billion yuan.

The company sells infant milk formula in more than 100,000 stores and has over 5,400 employees in China, according to data from Bloomberg.

Though statistics show domestic producers’ overall market share is growing, UOB’s Yuen said this is essentially a one-company achievement.

The 2008 melamine scandal is “still in the minds of Chinese consumers,” he said, and companies most heavily implicated at the time would have to totally rebrand themselves to escape past associations and do well.

“Aside from the Feihe’s success, I cannot pick up any immediate domestic brand that is really strong right now,” said Yuen. “It is more [a matter of] momentum from a brand specifically winning consumer confidence and minds, than a whole industry wave with consumers buying domestic [brands] because they’ve forgotten the melamine scandal.”

In November, Morgan Stanley-backed Feihe listed in Hong Kong for HK$6.7 billion, after chairman Youbin Leng delisted the then holding company, Flying Crane, in the US in 2013. Over the years it has built a reputation for transparency, quality controls and making products as close as possible to Chinese mothers’ breast milk, with a focus on premium products.

Feihe’s stock has soared by 66 per cent since its listing in November.

According to CCBIS, it has 25 quality control procedures with over 300 checkpoints, from inspecting the food given to the cattle, through to product delivery.

“Feihe was one of the very few infant formula companies that did not have any melamine crisis,” said Leng. “A big reason was that we were the first to set up a complete vertical integration system.

“At the time of the melamine crisis, we owned two of the dairy farms so the safety of not just the milk that went into our infant formula, but the feed of what the cows ate … and that quality, was also ensured.”

Chinese cities are categorised into tiers, with the biggest, most advanced and wealthiest in tier 1.

Even Feihe’s strongest customer network is in lower tier, less wealthy cities, according to brokerage CCB International Securities (CCBIS), though it has been expanding into top tier cities in recent years.

Meanwhile other scandals – like the substandard vaccines given to Chinese babies in 2018 – have only added to consumer worries stemming from the melamine scandal about a lack of transparency in the quality of infant products.

Some brands are using crises like the current coronavirus outbreak as a way to foster customer bonds, with Danone and Feihe launching free online medical consultation services for patients. Both have also been delivering products for free, and Feihe has donated 100 million yuan to the China Red Cross Foundation.

“It’s not the domestic brands, per se, that consumers do not trust, but the lack of transparency in quality management, as well as local governments’ over-willingness to protect their local champions to ensure growth and employment,” said EIU’s Wang.

Last June, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) set a goal for domestic baby milk formula producers to take a more than 60 per cent share of the national market, in a clear signal that Beijing is trying to reduce reliance on imported milk formula and make domestic companies more competitive. It did not set a deadline for this target.