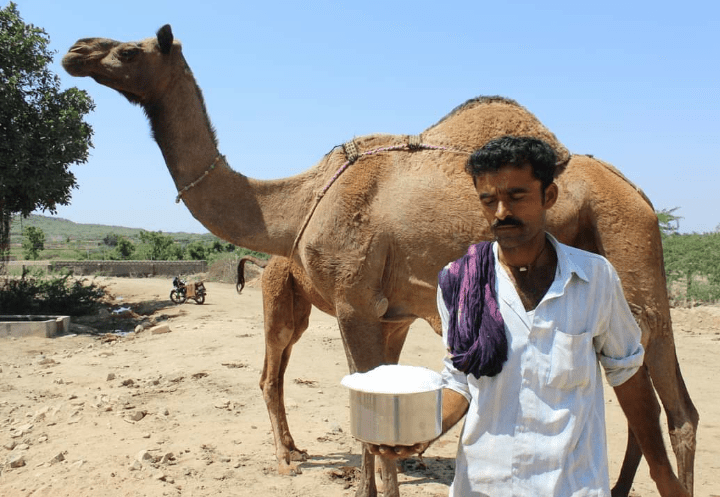

Camel milk, found to be a healthier option for people with diabetes and those with food allergies, can be the source of sustenance for camel rearers.

Several small dairies and Amul are selling camel milk and its products to city clientele, but there are many gaps.

A woman from Mumbai tweeted to Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the middle of the lockdown on April 4, requesting him to arrange camel milk for her 3.5-year-old son living with autism and severe food allergies. “He survives on camel milk and a limited quantity of pulses. When the lockdown started, I didn’t have enough camel milk to last this long. Help me get camel milk or its powder from Sadri (Rajasthan),” she wrote.

IPS officer Arun Bothra saw the tweet and reached out to railways officials. An unscheduled stop was arranged for a parcel train at Falna station in Pali district of Rajasthan from where 20 litres of frozen camel milk and 20 kg milk powder were picked up. The parcel finally reached the family on April 10, earning praise for Bothra and the Indian Railways from netizens.

The incident also brought significant publicity for camel milk. “Many parents of children with autism and food allergies approached us,” said Hanwant Singh of Camel Charisma, a dairy of camel rearers in Rajasthan, which provided milk to the Mumbai family. “We were able to send the milk as far as Kolkata and Odisha with the help of a special programme of the Indian Railways, running during the initial phase of the lockdown when no other transport facility was available. The sale almost doubled during those days.”

Other sellers also saw a rise in orders and enquiries. “Covid-19 has put greater focus on immunity boosters and we are seeing more interest in our products,” said Shrey Kumar, co-founder at Aadvik Foods, a startup selling camel milk products since 2016.

The benefits of camel milk have always been known to their rearers. They survive on it when out grazing their caravans for days. Several studies on camel milk have found its positive impact on autism, diabetes, liver disease, jaundice and even cancer. The milk is high in vitamin C, many minerals and immunoglobulins, which boost the immune system.

“We have several diabetics and cancer patients as our regular customers, besides around 520 families of children with autism,” said Singh.

A 2016 review of 24 studies on human and animal trials found that consumption of camel milk helped in cases of diabetes, cancer, colitis, Salmonella infections, heavy metal and alcohol-induced toxicity, and autism. However, the review points out that the current evidence is limited and more, better-designed studies need to be done.

Dr. Pritpal Singh of Baba Farid Centre for Special Children in Faridkot, Punjab, has 25 child patients taking camel milk. “It is a good alternative for autistic children who can’t digest cow or buffalo milk. Camel milk improves their gut flora, which helps with attention span and social behaviour,” he said while cautioning that we should refrain from branding camel milk as a cure. “Many companies market camel milk as the ultimate solution to autism, but that’s far from the truth. It’s just a tool to manage autism, not a cure.”

Milk business to sustain camel populations

The business of camel milk is crucial for the survival of Indian camels, which has fallen out of favour over the years as a draught animal. Earlier, camels were used for transportation, farming and border patrolling by the Border Security Force (BSF). Two-wheelers, tractors and all-terrain vehicles have now edged them out. There is little use for these humped beauties now, except in ferrying tourists in desert safaris. According to the 20th Livestock Census released in 2019, the camel population declined by 37.5 percent to 2.5 lakh from the 4 lakh registered in the previous census published in 2012.

The National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources has registered nine breeds of camel, of which five (Bikaneri, Jaisalmeri, Jalori, Marwari and Mewari) originated in Rajasthan, while two (Kutchi and Kharai) have Gujarat as their home tract, one (Malvi) belongs to Madhya Pradesh and Mewati breed is distributed in areas of both Rajasthan and Haryana. A small population of the double-humped camel also exists in the Nubra valley of the Ladakh region. Kharai is a breed specific to coastal areas of the Kutch region in Gujarat and is famous for its ability to swim.

Rajasthan, which holds the maximum share of camel population in the country, declared it the state animal in 2014 and banned its sale or movement outside the state due to concerns that it was being slaughtered for meat. This further dented the market. Famous camel fairs at Pushkar and other places declined in scale and the selling price crashed. “Before the law came into effect, a male camel used to sell for Rs 10,000 to Rs 50,000. Now it fetches only up to Rs 1,500,” said Hanwant Singh. “There is an unprecedented rise in the number of stray camels in Rajasthan.”

Hence, milk of the female camel remains the only hope for sustaining the present population, even though it goes against the traditional norms of the rearers. The Raika community, the traditional camel keepers of Rajasthan, trace their origin to Lord Shiva. They believe he created them to take care of the camel, a beloved animal of his wife, Parvati. The camel milk was never to be sold. It could only be given for free to whosoever needs it. Same is the case with Maldharis of Gujarat, who consider camel rearing a mandate from God and its milk a gift.

“At the root of this belief is the need to prioritise the nutritional requirements of the family. Sale of milk was also not required earlier because the trade of male camels sustained the rearers,” said Ramesh Bhatti of Sahjeevan Trust, a non-profit organisation working towards camel conservation in Gujarat. “It was difficult to convince them to start selling milk. Some families still keep a few camels reserved for the deity and their milk is not sold.”

Camel milk was not classified as an edible substance until December 2016, when the Food Safety and Standard Authority of India (FSSAI) came out with standards for camel milk to be sold commercially. The decision came after a sustained campaign by NGOs and camel breeders’ groups and subsequent support of Gujarat government for the same.

Today, small dairies are operating from Jaipur, Jaisalmer, and Pali in Rajasthan. Milk is supplied to local and inter-state customers in metro cities, but there is no organised market. In Gujarat’s Kutch region, the scale is bigger due to dedicated milk plants and the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF).

Products like chocolate, ghee, cheese, skin creams and soaps are also being made from camel milk.

Boost to the local economy

Kama Rabari (25) manages a herd of 50 Kutchi camels with his brother at Sanosara village in Kutch district of Gujarat. Of these, 20 are milch camels. Till some time back, Kama worked at a power plant around 70 km away from home on a salary of Rs 10,000 monthly.

“Today, I make Rs 1,000-2,000 per day staying at home by selling milk,” he said. “When I heard that companies are buying camel milk, I did not feel like continuing in the job (at the power plant). There is dignity in this work.”

Camel milk sells at a premium of Rs. 50 per litre in Kutch as compared to Rs. 38-40 for buffalo milk. The increased income has led to reverse migration in several villages of Kutch and the rearers are also increasing their stocks.

“When we held meetings initially to motivate camel owners, only old or middle-aged men used to attend. As the money started flowing, their sons took over,” said Mahendra Bhanani, co-ordinator of the camel programme with Sahjeevan. “The young men who had moved to cities for small jobs have come back and bought motorcycles to transport milk to the collection points every day. The going rate of a milch camel has gone up from Rs. 8,000-10,000 a few years back to Rs. 30,000 now.”

In 2016, Aadvik Foods started collecting camel milk from Kutch and now has a chilling and pasteurisation plant in the region, which processes around 20,000 litres of milk every month. In 2015, the Gujarat government announced a grant of Rs. 3.5 crore for Sarhad Dairy, a member of the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF), to set up a chilling plant for camel milk. The plant, collecting 2,000 litres of camel milk daily, sells processed milk and milk products under GCMMF’s brand, Amul.

“Around 150-200 families are engaged in selling of camel milk in Kutch,” says Bhatti. “Camel keepers in neighbouring districts are now demanding that milk chillers be set-up in their areas as well.”

Gaps in infrastructure

Low awareness about camel milk’s benefits, lack of infrastructure (especially bulk milk coolers in remote areas) and shrinking pastures for grazing are the limitations that need to be addressed for this dairy segment to flourish.

Chilling tanks and pasteurisers are essential for collection, processing and marketing on a large scale. Gujarat government’s support to Sarhad Dairy was crucial in setting up its plant in Kutch that improved the local economy. Rajasthan is yet to see such an initiative, even though news about a policy initiative in this direction keeps making rounds.

“There have been proposals in past and even though the government is aware of the need to market camel milk, nothing concrete has come up yet,” said Anshul Ojha of the non-profit Urmul Trust, which has been working with camel rearers in western Rajasthan and recently set up a 1,000 litre chilling plant at Pokhran in Jaisalmer district. “Marketing and distribution are other challenges. We wish to collaborate with like-minded people in cities to promote camel milk consumption.”

While Camel Charisma has been sending frozen milk through buses and trains to customers, Sarhad Dairy was initially selling frozen milk with a shelf life of five days only in the cities of Gujarat. “Now, with ultra-high temperature technology, we are able to increase the milk’s shelf life to 180 days,” said Nilesh Jalamkar, plant manager of Sarhad Dairy at Bhuj. “It can be easily stored and distributed to other parts of India.”

Aadvik Foods, on the other hand, is banking on milk powder. “It is logistically easier to store and transport with minimal impact on quality. We have also exported to the United States and the Middle East,” said Kumar.

The high cost of camel milk also means that it is restricted mostly to a niche clientele who can’t do without it, like families of children living with autism and food allergies. Amul’s 200 ml PET bottle comes for Rs. 25 while Camel Charisma sells frozen camel milk for Rs. 250-300 per litre and Aadvik’s freeze-dried milk powder costs Rs. 3,325 per 500 gm.

“There is very less quantum of camel milk available for the market. Collection from remote areas, cold chain storage, processing and distribution make it a costly affair as compared to cow milk, which can be collected and sold locally,” said Jalamkar. “If there is an increase in business, the cost of operations may also come down.”

Restricted demand is also why the milk plants had to stop collection intermittently in the past after reaching their saturation levels. “There have been times when the collection would stop for a week because they can’t store as much milk,” said Kama. “Thankfully, Sarhad dairy has been collecting without any break for the last six months to make milk powder. This helped us make money even during the lockdown.”

The domestic market of Rajasthan and Gujarat can be tapped to overcome the challenges of collection and distribution. “Rajasthan has a big market for sweets which can be explored for the use of camel milk. These might turn out to be a good alternative for people with diabetes and those seeking low-fat varieties,” said Ojha.

Shrinking pastures

The camel is a free-ranging animal, walking 8-10 km in a day, munching on leaves of trees in forests, pastures, or fallow farms.

Encroachments and development projects are shrinking common pasture lands, while farms are increasingly fenced and are more intensively cropped than earlier due to the expansion of irrigation facilities.

“Till 20 years back, farms used to be fallow for eight months and there was no fencing. Herders and farmers used to have a symbiotic relationship, which has now broken because chemical fertilisers have replaced animal manure,” said Hanwant Singh. “Solar and wind energy parks have come up on pasture lands while notified forest areas are increasingly becoming out of reach of herders.”

Raikas would get grazing permits to enter the Kumbhalgarh Wildlife Sanctuary in Rajsamand district of Rajasthan. Forest officials banned the practice in 2004, citing a letter from Supreme Court’s central empowered committee that recommended a check on commercial activities and grazing. “Even though the Forest Rights Act was enacted in 2006 and hence overrules all previous orders, the forest department continues to uphold the 2004 letter,” said Singh. “Now, herders from around 80 villages are preparing to approach the Supreme Court for settlement of their grazing rights.”

In Gujarat, the Kharai camel, a breed specific to coastal areas of Kutch, has been largely impacted by industrial projects in the region. Kharai camels are dependent on mangroves for food, but many ports and factories have either damaged mangroves or blocked access to them, thus impacting the population of camels in the region. “Tundavandh, a coastal village, for example, has lost 80 percent of its camels in the space of 15 years due to restrictions on accessing the mangroves,” said Bhatti.

The issue was raised at the National Green Tribunal, which ordered the authorities to remove obstructions and ensure free flow of estuarine water in the creeks.

Even as things are starting to look up, it’s still a long haul for camels and their bearers.