How safe is the milk you drink? In a 2020 report published by the Consumer Guidance Society of India (CGSI), 79% of branded or loosely packed milk in Maharashtra was adulterated. In other words, barely 21% of the samples tested by CGSI complied with the standards specified by the Food Safety and Standard Authority of India (FSSAI).

The problem of milk adulteration is not confined to only one state. In states like Punjab, for example, there are regular reports of raids being conducted by the state against illegal factories making spurious milk and milk products.

Responding to the challenge, Punjab-based AgNext Technologies, an Ag-Tech startup, has innovated a Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy-based rapid milk quality assessment solution that measures milk samples to provide a complete nutrition profile—including fat, solid-not-fats (SNF), proteins and added water.

It also tests for the presence of adulterants, such as melamine, vegetable oil, maltodextrin, detergent, urea, starch, sugar and salt, amongst others, in just 40 to 45 seconds.

Moreover, the startup says that milk samples can be tested quickly and efficiently with 99% accuracy as compared to laboratory testing using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms. This helps catch milk adulterations early to prevent them from entering the dairy supply chain altogether.

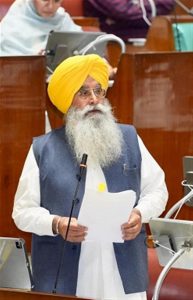

“The testing equipment is an IoT-enabled, AI-powered, handheld, battery operated device. The data is fed into Qualix—AgNext’s cloud-based SaaS platform—which helps provide a collective visualisation of information across locations, allowing businesses to fast track data-led procurement decisions. This augments and replaces the intuitive and sensory method of milk testing with an unbiased scientific measurement,” says Taranjeet Singh Bhamra, founder and CEO of AgNext Technologies, speaking to The Better India.

Type of adulterants typically found

Among the most common kinds of adulterants found in India is vegetable oil. Milk suppliers and other stakeholders in the value chain extract the fat present in milk and replace it with oil to keep the base value of fat the same. Conventional equipment such as the lactometer cannot detect it, while organoleptic testing (testing by tasting) is not reliable or scalable.

“Let’s say there is 8% animal fat in the fresh milk extracted from a buffalo. There are very sophisticated ways of extracting, say, 6% of that fat, leaving only 2%. When they sell the milk, the reading on the lactometer will still show 8% fat. When the milk goes to a factory or a processing centre and a company wants to make ghee out of it, they will only get a yield of 2%, because the rest is vegetable fat. The 6% extracted is sold as ghee, which fetches a much higher price. Typically, the person gets about Rs 500 per kg for ghee and the replaced vegetable oil is bought for around Rs 80-100 per kg. Thus, they are making Rs 400 from the 6% of the fat taken out. Sometimes, people add vegetable oil to the existing fat, which also fetches a higher price,” Taranjeet explains.

The other form is solid-not-fat (SNF)-based adulteration, which includes urea, maltodextrin, starch and sugar. These adulterants are mixed into the milk to raise the SNF value, which fetches a higher price in the market. “No one is deliberately out there to supply substandard or adulterated milk, but it’s a question of economic incentives,” he adds.

Instant testing over delays

A key reason why milk adulteration remains largely prevalent in India is the lack of testing for adulterants on-site when milk is collected from the farmers.

When a farmer arrives at the plant to sell the milk, it is tested only for fat percentage and SNF with the help of ultrasonic devices. The resultant measurement helps set the price of the milk. Adulterants are added to adjust these parameters and enhance the milk quality in a test. While some ingredients such as urea are naturally found, there are permissible levels set. The permissible level of urea content in milk is set at 70mg per 100ml, as per the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India Act 2006 and Prevention of Food Adulteration Rules 1955.

“Beyond this, the quality of milk is determined through the conventional method of organoleptic testing, a sensory method which entails checking the colour, smell and taste of the milk to measure quality. If the milk grader has any doubt about the quality, the sample is sent ahead for chemical testing separately. Otherwise, milk gathered from various farmers is collected together in a large vat and then sent for chemical testing. However, now owing to the large sample size, adulterations can become heavily diluted and may not be captured when the collective milk sample is tested in a lab. This makes adulteration difficult to decipher,” says Taranjeet.

This mode of testing is subjective, non-standardised and inefficient. Milk adulterations are becoming increasingly sophisticated to pass organoleptic tests. Thus, it’s important to test the composition and adulteration of milk as soon as it is brought by the farmer.

So, how do you test for milk adulteration in the device developed by AgNext?

The process is very simple. A small milk sample is extracted from a farmer’s can and collected in a simple cuvette (a small test tube). This sample is inserted into the device, and within 40 seconds, they obtain the entire profile of the milk—fat content, SNF, and all other kinds of adulterations.

No internet connection is required to operate the device, though connectivity is required to store data into the Qualix platform. The device works using a battery instead. It has been used across farm gates, warehouses, collection centres and factories of major dairy-business enterprises and is portable and lightweight. One can charge these devices with a power bank, and they don’t need a regular supply of electricity—a major concern in village collection centres.

The device is connected to a mobile phone via Bluetooth, which is further connected to the Cloud and AgNext systems. Besides its ability to seamlessly integrate multiple enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems through communication interfaces, the device is dust and water-resistant and can function across a range of climatic conditions.

“We collect data about the milk delivered by individual farmers, cooperative societies and villages every day. Over a period of time, you can develop all sorts of history about where better fat or SNF-content milk comes from and what kind of quality-based pricing you need to build. Thanks to our technology, companies have all the necessary data on their respective phones to make decisions about whether to buy milk from a given cooperative, for what price, and whether it’s of the requisite quality,” he says.

Typically, at a milk collection centre, where 50-100 farmers come to deliver at a time, the objective is to test their product in as little time as possible. The industry average for milk testing for fat and SNF only is about 30 to 35 seconds. Although AgNext’s device takes about 10 seconds more, it’s also testing for a whole host of adulterants.

Having said that, these devices don’t work in isolation. They need to be integrated with the weighment machines, ERPs and payment systems. Besides installing these devices, the startup is working with their clients to integrate them with these key elements as well. Currently, they also store all their data and provide it to clients via the Cloud.

“We need not have more than one device in a given collection or chilling centre, but we need to integrate all the other elements. The figure of 99% accuracy comes from clients who have tested our device in NABL (National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories)-approved laboratories. Besides, we are also working with the National Dairy Research Institute (NDRI) to validate our device, which will likely happen in another two months,” adds Taranjeet.

Currently, the startup has orders to deploy their technology in over 5,000 locations across cooperative societies, collection centres, chilling centres and milk processing multinational companies.

Over the last year, more than 200 milk cooperative societies in Punjab, West Bengal and Haryana have started adopting their device. Overall, these machines have been employed in over 300 locations. Discussions are currently underway with cooperative societies in Rajasthan, Gujarat and Maharashtra.

Developing algorithms

When it comes to algorithms, more data means greater accuracy.

“We have collected over 70,000 milk samples, with each measuring anywhere between 0.5 to 1 litre. These are fresh samples collected from the ground during the milking process to ensure purity. As a result, we have a vast array of data points that allow us to attain accuracy rates of 99% or more. Having said that, we first implemented the algorithm after collecting 20,000 samples, but to make it more accurate, we kept ingesting more data. The error rate on our devices largely comes from human errors such as not inserting the cuvette thoroughly. Although it’s a very simple process, we are training stakeholders. As these stakeholders in the milk business get more sophisticated in the kind of adulterants they employ, so will our technology. We are one step ahead. This is how we are digitising testing, traceability and accuracy,” claims Taranjeet.

It has only been a year since AgNext has deployed these devices on ground, but prior to that, the startup spent about two years building and testing the hardware and algorithm.

“Our tech benefits businesses and milk farmers and we will continue to witness the positive impact of our work. The business model we have created—where we only charge businesses for every transaction and not milk farmers for using Qualix—is creating waves. This will be the ‘go-to’ model for building a more sustainable impact in the dairy sector,” he says.

(Edited by Divya Sethu)